Mankell Family History

"Lonely Gravestone Tells of Pioneer's Fate: Johannes Iverson"

written by Orlynn Mankell

Storyteller and historian, Orlynn Mankell

From the "Territorial Journal" section of The Land, May 16, 1983:

In West Central Minnesota, often in remote and out-of-the-way places, there remain little reminders of a time when the regions were a part of America's far western frontier.

In Kandiyohi County, north of Willmar, is the quiet and unobtrusive Crook Lake. This attractive mile-long lake has always been unique in that it still seems to retain appealing remoteness.

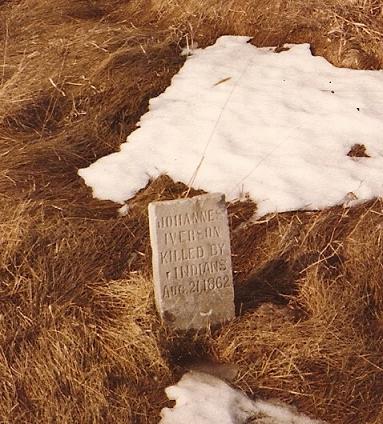

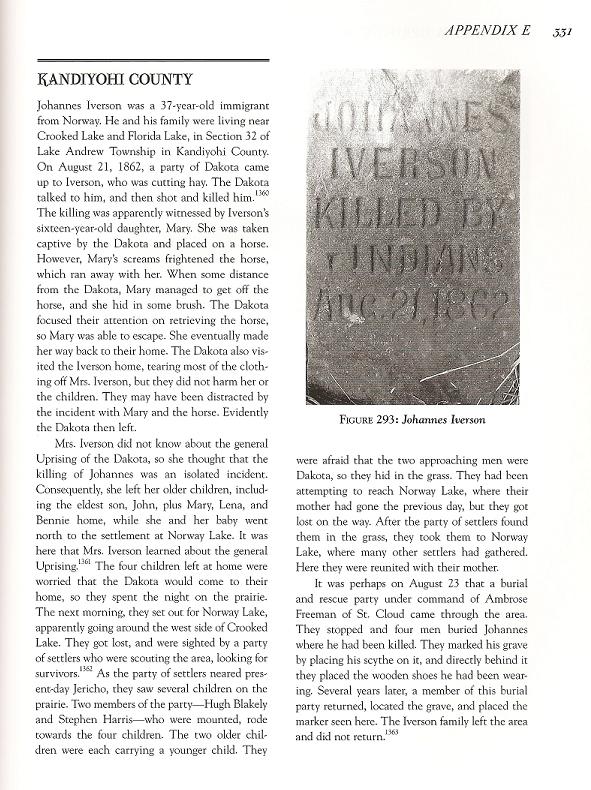

Away from the lake, down in a ravine, a small rectangular stone protrudes from a small meadow. This marks the lonely and solitary grave of early Norwegian immigrant, Johannes Iverson. On the stone is the simple but compelling inscription "Johannes Iverson, Killed by Indians, August 21, 1862."

Grave marker for Johannes Iverson, 1862

Johannes Iverson was 37 when he saw Crook Lake for the first time in the summer of 1858. He established his own personal beachhead along the shores of the lake in the form of a pre-emption claim.

This farmer would have been well advised not to be where he was on August 21, 1862, but it was a clear, warm day and perfect weather for cutting hay on the farm. But unknown to him was that much of central Minnesota was in a state of upheaval of Sioux Indian War, which was leaving fire and death in its wake.

Just the day before, this revolt had reached about eight miles to the northwest where a small Swedish colony had come under attack and now ceased to exist. Three miles to the south, Norwegian farmers were cut down in their farmyard. But in this isolated position this was all unknown to Johannes Iverson. As he saw it, it would be just another day on the farm.

Across the prairies to the south, about a mile away, a party of horsemen proceeded slowly in his directions -- 12 or 13 in number. Also in the area was Iverson's 16 year-old daughter, Mary. The farmer had always gotten along well with these people. As he looked up now and then from his scythe, he knew them to be Sioux Indian hunters coming up on another one of their hunting trips, up to their old hereditary hunting grounds, the Norway Lake "Big Woods" which lay four miles to the north. They had come across his claim several times before and after four years, Iverson had come to know them fairly well. These mounted hunters closed the distance in a slow, leisurely pace -- it was up a small hill then down the other side.

About an acre of hay had been cut by this time and had been raked into neat careful windrows for drying. Still maintaining this "just passing by" appearance, the "hunters" rode up.

A curious little scene then unfolded on Minnesota's western prairies. According to Mary, who was about a quarter mile away, there was nothing to indicate that there was something different on this particular day. There would be a brief visit before continuing on. As usual, they were well armed but then, as hunters, this was the way they had always come before.

Probably Iverson's major mistake was that he had not been keeping up with neighborhood events. Bet then, even those who had heard about the startling disaster sweeping across much of Minnesota were finding it hard to believe.

Johannes Iverson received his visitors. One record states that a few of them leaned down for their horses and shook hands with the farmer. "They engaged him in conversation", from another account. And the somewhat intriguing questions of what they talked about and if there was a language barrier of any kind will always be unanswered.

This nefarious expedition originated two days before along the Minnesota River. As they sat on their horses and looked down at their old friend and benefactor, it may be that the real reason for this particular visit was getting just a little difficult to carry out. But it was time to be moving along and it was then that a member of the party raised his rifle and shot the farmer dead.

It would go without saying that his peaceful Norwegian farmer had certainly not deserved anything like this. He had always gotten along well with these people, had always treated them with courtesy and respect, and on this fateful day was doing nothing more provocative than cutting hay for his cattle for the coming winter.

But, as seen through the eyes of the tribesmen, Johannes Iverson had nevertheless committed certain unpardonable sins. He was white and secondly, he was where he happened to be. The war party then urged their horses ahead as they resumed their leisurely trip.

So ended this climactic last and final visit on the remote upland prairie along Crook Lake. And so ended the four-year sojourn of Johannes Iverson into the New World.

Mary, stunned and horrified at what had happened, fled back to the cabin where she and other family members hid in tall grass and thickets for the rest of the day. A frightening night was to follow. After the harrowing events of the day, every tree, every shadow, had suddenly now become a threatening Sioux Indian warrior. The family was discovered the following day and eventually arrived safely at St. Cloud.

The exact day is unclear but it was about August 23, 1862 that the men of Freeman's company from Paynesville, rode around the west end of Crook Lake. The body of Johannes Iverson still lay where he had fallen. Captain Freeman took a quick close-up look and appointed four men for burial duty.

This burial detail left fairly good records. The farmer's burial place was prepared right where he had fallen. After the last earth was returned and smoothed down, they laid the farmer's scythe on top and directly behind it they placed the wooden shoes which he had been wearing. No one really knows for how long this plot would remain marked in this somewhat different way.

The company then left, heading in the same direction as the Indian party two days before. That evening Freeman's men made camp along the west shore of Nest Lake. Freeman's colorful organization provided a valuable service on the now abandoned and depopulated frontier. Their activities included watching for stragglers, rounding up stray cattle and securing household goods and valuables from hastily abandoned cabins. After two months the company disbanded.

Several years later, a member of Captain Freeman's old burial detail returned to Crook Lake, found the burial place and where the marker was placed. The family of Johannes Iverson eventually left the area, leaving no descendants here [see updates below]. The gravesite remains almost forgotten. It is visited only rarely. For many years grazing cattle kept the site neat and trimmed. And so it remains today with its turbulent beginnings, and where not for 120 years the winter snows have drifted over it and then receded.

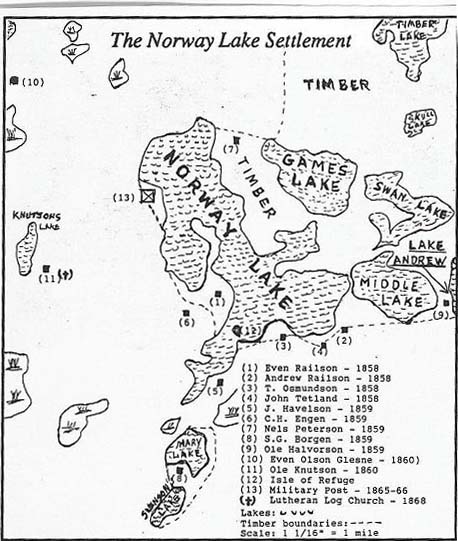

Map of Norway Lake Settlement, noting Sven Gunderson Borgen cabin, Thomas Osmundson farm

and Norway Lake with the Isle of Refuge near the Osmundson home.

The Iverson farm and Crook Lake (not on the map) are about 3.5 miles south of Norway Lake.

Source: Keeping the Faith...Sharing the Faith

Iverson's wife, children and descendants, updates written by Carolyn Sowinski.

There is more information about Iverson's widow and family, events in August 1862, and their lives after Johannes's death. Information has been provided by descendants; in state and federal census data; a Gabriel Stene article in the Willmar Tribune (March 17, 1926); church histories; county and marriage records. Daughter Mary, who witnessed her father's death, was briefly captured by the Dakota Indians who put her on a pony. She scared the pony away from her captors, escaped and hid. Later Mary left via the east side of Crook Lake, found her way northeast to Paynesville, and was separated from her family for several days.

Mrs. Iverson and her two youngest children (Sophia and baby Peter) went straight north from Crook Lake for three miles to the Thomas Osmundson farm on the south side of Norway Lake. Mrs. Iverson and her two children were taken to the Isle of Refuge in Norway Lake where other settlers had taken refuge from the killings. Her 3 other children (John, Lena and Bennie) went around the west side of Crook Lake, over the prairie, to the Sven Gunderson Borgen's cabin and farm. The cabin was deserted because Sven, Margit, and Gunder had left for safety on the Isle of Refuge. The Iverson children took shelter in the cabin's cellar. The next morning Sven Borgen and Gunder returned to their home to take belongings for their long journey with other settlers to St. Cloud. They found the young children hiding in the cellar and brought them to the Isle of Refuge where the children were reunited with their mother and siblings. The Iverson family traveled to Forest City, Meeker County (southeast of Paynesville). Mary reunited with her family. (There are written discrepancies regarding where Mrs. Iverson reunited with daughter Mary: at the Isle of Refuge, near Paynesville, or near St. Cloud.)

Kari (Johnsdatter) and Johannes Iverson were from Hurdal, Akershus, Norway and immigrated to the U.S. in 1852 with children John and Mary (aka Alvina Betsey Marie). The family first settled in Wisconsin where children Bennett and Lina were born, then came to the farm near Crook Lake, Monongalia County Minnesota around 1858 where Sophia (Maggie) and Peter were born. After the death of her husband in August 1862, widow Kari Iverson (aka Carrie, 1823-1886) married her Crook Lake neighbor and Swedish immigrant settler, Ole Dahl, on October 8, 1866. Thomas Osmundson was a witness; Andrew Railson was the Justice of the Peace. In 1869 the Probate Court of Monongalia County appointed Thomas Osmundson as the guardian to the children (Mary, John, Bennett, Lena, Maggie, Peter), heirs of John Iverson. Kari and Ole Dahl had a son, born c1867. The family lived by Crook Lake for a few more years. The marriage didn't last. Ole Dahl left his family for the Dakota Territory where he died. Kari stayed in Kandiyohi County. The 1875 state census data records her as using the name Carrie Iverson, no longer "Dahl". The 1880 federal census registers Kari and her son Regus in Harrison Township, in the eastern part of the county. In 1885 she lived in neighboring Gennessee Township, near her son John. Kari Iverson died in 1886 and is buried in the Bethlehem Lutheran Cemetery, Atwater, Minnesota, where her son John is also buried.

The children:

- Mary (Alvina Marie, 1849-1920) married Eric Alexander Bergman in 1873. They had 6 children and lived in Swift County MN and later, Saskatchewan Canada.

- John Andrew (1851-1909) changed the spelling of his last name to "Everson" to better reflect the correct pronunciation of the Norwegian name. John married Christine Lund in 1889 and farmed west of Atwater in Section 5, Gennessee Township. John and Christine had 3 sons: William, Alexander and Benjamin. Alex's descendants remain in the Atwater area. The family's 7th generation is on the John Everson farm.

- Bennett Martin (1856-1926) married Christine Thompson in 1882. They had 6 children and lived in Pope County, MN.

- Lina Caroline (1858-1892) married Nels O. Johnson in 1881 and lived in Section 16, Gennessee Township; they had three children.

- Sophia Margaretha (1860-1911) married Lyman Wells in 1883 and lived in Stearns County, MN.

- Lewis Peter (1861-1939) married Mathilda Johansson in 1889 moved to Otter Tail County, MN and later, Cass County ND. They were parents of 8 children.

- Kari and Ole's son Regus Olson Dahl (Regu, 1867-1937) married Anna Rockstad (Rakstad) in 1896 at South Lake Johanna Lutheran Church in Kandiyohi County. They had 7 children, lived in North Dakota and later in Canada. He died in 1937 and is buried in Estevan, Saskatchewan.

Three views of the Isle of Refuge:

Isle of Refuge, 2012.

Winter view of the Isle of Refuge, 1974.

Aerial view of the Isle of Refuge, 2012.

Updates:

There are recently published books about the 1862 Dakota War/Sioux Uprising. Dakota Dawn, The Decisive First Week of the Sioux Uprising, August 17-24, 1862 written by Gregory F. Michno and published in 2011, provides chilling descriptions of the events near New Ulm along the Minnesota River, in Kandiyohi County, and other areas in Minnesota. The Iverson family story (pages 283-285) is part of the larger narrative of events in the Norway Lake and Monson Lake settlements, where survivors fled to the Isle of Refuge.

Dakota Uprising, a Pictorial History, written by Curtis Dahlin, writes about the Iverson family on page 331 (a copy is included below). Be sure to read two endnotes-- #1360 and #1363 (page 385; a copy is included below) where Mr. Dahlin tells of his visit to the site of Johannes' death.

Title Page

The Johannes Iverson story.

Endnotes #1360 and #1363 are of interest!

Bibliography: The Land and Willmar Tribune.

Orlynn's articles about Kandiyohi County history:

- Why the Dakota loved Kandiyohi County

- Gunder Swenson, Norwegian Settler

- Thomas and Bergit Osmundson

- Pioneer Woman: Anne Christopherson Olson Holter

- Lonely Gravestone Tells of Pioneer's Fate: Johannes Iverson

- 1863 Drought in Kandiyohi County

- Norway Lake Pioneer (Sven Borgen) Endured Drought of 1863

- Threshing Machine

- Lake Florida Mission Church