Mankell Family History

"Norway Lake Pioneer Endured 1863 Drought"

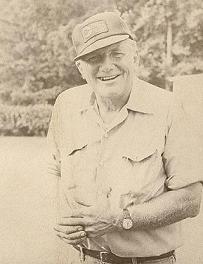

written by Orlynn Mankell

written by Orlynn Mankell

Storyteller and historian, Orlynn Mankell

From the The Land, October 4, 1982

One of the most severe droughts ever to visit western Minnesota and the Dakotas was during the early years of 1863-64. This comes almost before any records for the regions. In a practical sense there was no one here for the dry season to affect, but there were a scattered, isolated few.

One of these early pioneers was Norwegian Swen (Sven) Gunderson Borgen. He and his family had come to the Norway Lake region of northwestern Kandiyohi County in the summer of 1860.

Not far from Norway Lake is the small lake, Lake Mary, where Swen had taken an early pre-emption claim. He spent most of the remaining part of the season building a cabin in an oak grove along this quiet lake. For a time this cabin stood on the extreme western limits of Minnesota civilization. To the west lay the endless prairie wilderness, virtually uninhabited, and broken up with lakes and groves.

By 1862 the Norway Lake settlement consisted of about nine families. The crops were good for the season, but several accounts state there had been barely enough rain to produce them. it was the beginning of a severe, two-year drought.

This frontier colony was caught up in the hostilities of the Sioux Indian War (or Dacohtah War) of August, 1862, which reached up into the northern half of Kandiyohi County on August 20, leaving about 25 people dead. Sixteen of those were within a six mile radius of Swen's cabin. Consequently Norway Lake was abandoned.

Several of these displaced settler families from Norway Lake, along with others from the surrounding regions, assembled 70 miles to the northeast along the St. Francis River northeast of St. Cloud. Among them were the two cows belonging to Swen.

During the time when there was no one there, a severe drought affected Norway Lake, western Minnesota, and the Dakotas.

A year later, in the summer of 1863, reports reached St. Francis that the war parties had disappeared from Kandiyohi County, but the entire area had been sealed off by the state. Only military traffic was permitted. Certain exceptions were granted so farmers could make temporary visits back to their farms. One of these was Swen.

He had decided that he would make repairs to the cabin (assuming there was something left to repair). Then he would put up a small stack of hay for feed cattle if the family should return out of the grazing season. Swen wanted everything ready for the return--whenever that would be. His 18-year old son, Gunder, accompanied him.

Taking a few provisions, Swen and Gunder left on foot toward the southwest. They spent the nights in buildings vacated during the outbreak. After being ferried across the Mississippi at St. Cloud, they crossed the military patrol line at Paynesville. It ran south through Paynesville to Ft. Ridgely.

In 1863 this line divided Minnesota into two parts: life as usual to the east, but with an enforced emptiness to the west. Crossing this line, Swen and Gunder entered the empty and depopulated Kandiyohi County. Drought conditions seemed to worsen as they headed west.

Their route took them along the north shore of the largest lake in the region, Green Lake. Here the drought was highly apparent. As the two looked out across this four or five mile-wide lake they hardly recognized it. Underwater bars crossed the lake from different directions. The lake was at an extremely low level, so low that these bars were all fully out of the water. These exposed bars, as Gunder remembered them, were many feet wide and crossed the lake giving the impression that the lake had divided itself into three parts.

In the 120 years since, there is no record of any similar three-part condition being seen on Green Lake. This includes the dry 1930s when just one part of these bars was above water.

Leaving Green Lake, the father and son continued west 12 miles to the farm, walking across empty prairie wilderness, around a couple of lakes and through hardwood groves. Swen wondered what he would find on the farm. He knew that during the hostilities of a year before many cabins and wheat stacks had been burned or damaged.

Gunder, Swen's son, best remembered the day the two arrived at the quarter-section farm. It was in the grip of a devastating drought. The familiar Lake Mary which lay directly below the cabin (and which was at low levels when they left) was now entirely dry. Throughout his long lifetime, Gunder would never see the lake dry again.

On that long-ago day, sometime in the middle of late summer of 1863, Swen opened the door to his cabin, walked in, and looked around him. Everything was just as he had left it one year before. This included the entire farm. Swen had always gotten along well with the Sioux hunting parties when they appeared around the cabin. One theory has it that it was because of these past considerations that nothing had been disturbed around the cabin or farm. It would probably be hard to say, but Swen's family and these colorful hunters had always treated each other well.

Swen and Gunder went out on the scorched and empty prairie. It was a scene of hot, dry desolation. The native prairie grass, which normally stood over knee-high, was now short, dry and shriveled. Nowhere on the farm or adjoining areas could grass of any length be found for hay. In later years Gunder would refer to his visit. His story was always direct and consistent: Green Lake in three parts; Lake Mary dry; no hay for two cows.

Cabins stood empty and silent in the deserted Norway Lake settlement. After staying at the cabin for two or three days, the two returned back to St. Francis.

The tedious winter of 1863-64 passed for these displaced Norwegians, living in some kind of exile east of St. Cloud. In one instance three families lived in three rooms. As the days wore on into the summer of '64, there was still no word when they might return. These, of course, were Civil War times and that was a factor in the delay.

Margit, Swen's wife, continued to milk the two cows. Gunder spent time hunting, which was a mainstay for many. After being gone for two years. Everyone was thinking of home--including Swen.

In the fall of 1864 the patrol lines were extended west, including Kandiyohi County and Norway Lake. A small military post along Norway Lake, staffed with men from Co. L, Second Minnesota Cavalry, was established. And it was with the coming of Company L that the Norway Lake settler families were free to return. The very first to do so was Swen Borgen, late in the fall of 1864.

The exile was over.

Most of the settler families did not return until early spring, 1865, during the closing days of the Civil War and just in time for the spring seeding. The Norway Lake settlement expanded rapidly in that post-Civil war westward migration.

This severe drought that beset the regions during 1863 and 1864 came to an end. It did not reappear in 1865. A soldier in the region looked around him one morning in the spring of that year and noted, "The sloughs were all full." Heavy rains were returning again to west central Minnesota.

Orlynn's articles about Kandiyohi County history:

- Why the Dakota loved Kandiyohi County

- Gunder Swenson, Norwegian Settler

- Thomas and Bergit Osmundson

- Pioneer Woman: Anne Christopherson Olson Holter

- Lonely Gravestone Tells of Pioneer's Fate: Johannes Iverson

- 1863 Drought in Kandiyohi County

- Norway Lake Pioneer (Sven Borgen) Endured Drought of 1863

- Threshing Machine

- Lake Florida Mission Church