Mankell Family History

The following articles, written by local historian Gabriel Stene, are extensive and colorful obituaries of Gunder Swenson and his wife Gemine Negaard Swenson. Gunder's obituary includes information about his life, focusing on his family's pioneer life and the 1862 Dakota War (Sioux Uprising) in central Minnesota. Gemine's obituary is filled with flowery and grand language.

Gunder Swenson:

"SKETCH AND INCIDENTS IN THE LIFE OF GUNDER SWENSON"

WILLMAR WEEKLY TRIBUNE

Wednesday, October 3, 1934

Sven Gunderson Borgen was born at Numedal, Norway, July 16, 1810, and died here at Norway Lake, November 27, 1904. Mrs. Margit Borgen was born at Hallingdal, Norway, March 15, 1812, and died July 26, 1891, here at the pioneer home. Their resting place is in the East Norway Lake cemetery.

Their son, Gunder Swenson, the subject of this sketch, was born Jan. 16, 1845. In the spring of 1857, with parents and two sisters – Ragnhild and Birgette, he migrated to America, arriving at Beloit, Rock Prairie, Rock County, Wisconsin. While the family lived here, Gunder was confirmed by Rev. Diderickson and his sister Birgette was married to Thomas Osmundson.

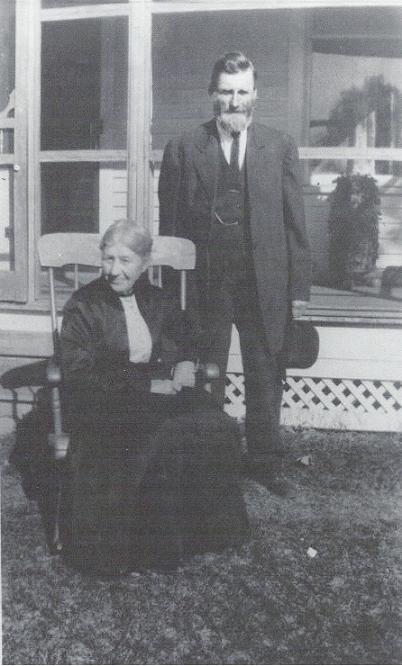

In the spring of 1859, a colony of a few families set out for the wild west. They traveled over poor roads, or no roads at all, zigzagging around hills and swamps, no roads being located on the section lines. They endured the plagues of Job, mosquitoes and horse flies pestered them. Ox-mobile and old covered wagons composed their emigrant outfits. They arrived at Norway Lake in the middle of the summer of 1859. The settled down and cooperated in the building of their first primitive homes of different styles – dug-outs, sod houses, shanties and small log cabins. See the large picture and note the old gentleman Borgen, Mr and Mrs. Gunder Swenson and some of the children.

In the cellar under that first cabin is where the three children of one of the colonists, Johannes Iverson – John, Lena and Bennie – hid and stayed all night, after their father was killed by the Indians while cutting grass with a scythe on the meadow and with wooden shoes on his feet.

The colonists lived together with and were familiar with the Indians during the first three years. There was not much faming in those days – no small grain, no place to deliver it and no railroads to carry it to market, even had they raised any quantity of it. Their flour was corn meal ground on a coffee mill. They caught fish and hunted wild game.

In the spring of 1860, Gunder said to his parents: I am tired of this living on corn meal all the time. I will strike off East until I find someone who has been raising small grain. I may find some work and get a little money with which I can buy some wheat to furnish us with wheat flour through the year.” So he started off finding the Henderson-Pembina trail, and followed it into what is now the Township of Acton in Meeker County. He slipped into a new settler’s home and asked to buy some dinner. “God bless you and us all, but we ourselves do not know where our next meal is coming from. But over there is a man who has laid in a little stock of groceries and you will find something to eat there. Gunder went there and had his dinner. This was the home of Robinson Jones, the place that two years later became a place of horror and were the great Indian Outbreak started – the place where the first blood was shed, the first live people were killed, and which has gone into the history of Minnesota. Gunder also asked for work. “Yes, I need one now through the summer. How old are you?” “Sixteen years.” “You are small for your age.” “Well take me on trial.” “I’ll tell you what I will do. I’ll give you fifteen bushels of wheat for the summer.” Gunder gladly accepted. Wheat was just what he wanted.

During that summer Gunder built a rail fence, which later figured in the start of the Indian troubles. In the corner of the same a hen had made its nest and laid a number of eggs. That Indian war was not planned by any chief or warrior. They were caught by surprise just as the whites were. Its inception was the work of four Indiana anarchists. The Indians had such lawless people as well as other people, who ignore all rule and order and would be under no command of chiefs or anyone else. Those Indians found the hen’s nest in the corner of the fence which Gunder Swenson built. One began to pick the eggs, but another said, “Don’t touch them. They belong to the whites. The other insisted. ”I am hungry and I want to eat them.” The first said, “Don’t’ touch them.” The first then threw the eggs on the ground and called the objector a coward. This expression started the blaze. “You’re so afraid of the whites that you would not dare to eat an egg if you were starving to death.” A hot quarrel followed. “I will show you that I am not a coward. I can shoot the whites. Do you dare follow me?” “Yes,” the other party said. “I can show you that I am no coward.” The other two Indians did not take part in the quarrel or the shooting but nevertheless accompanied their companions.

Jones was a widower with no children. But he adopted two orphan children who were related to him – Clara Wilson and her little brother who was three years old. Mrs. Baker was a widow and had a son named Howard, who was married and had two small children. They lived about a half mile east. So the old people married. It was at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Robinson Jones where Gunder had some for dinner and stayed and worked that summer of 1860.

On that fateful Sunday, August 17, 1862, Jones had been asked to dinner at Howard Baker’s. Mrs. Jones was already there when these four Indians came to Howard’s home. They offered to trade guns. A Mr. Webster had just arrived from Wisconsin with his young bride, was staying there, did their cooking on the stove, but used their covered wagon as sleeping apartment. He traded guns with the Indians and gave three dollars to boot.

The Indians suggested shooting at a target fastened on a lone tree. (This tree has long ago blown down but I have been standing by the stump.) They then all went to the house. Baker and Howard did not reload, the Indians did. They went over to Jones’ place evidently with the idea of buying whiskey for the three dollars. They were refused and became raving wild, and began to shoot in the air. Jones then went to Howard’s thinking the children were already there with Mrs. Jones. Just behind him came the Indians. Their first victim was Howard Baker. Then Mrs. Jones was shot, but managed to get up to run to the house, but was shot again and fell dead. Then Mr. Webster was shot. His young wife whom the Indians did not know was in the covered wagon, ran out with a gun, and frightened the Indians. Her husband died in her arms. Jones ran behind Webster’s wagon but did not escape, as the Indians laid him out with murderous aim. Then the Indians ran over to Jones’ place and shot Clara Wilson, who was standing in the door. The little boy escaped. Mrs. Howard and Mrs. Webster then took the two children and started toward the east. In their flight they met a Mr. Ingman to whom they told their sad story. He mounted a horse and rode to Forest City, gave the alarm, and a body of sixteen men were soon at the scene of the tragedy. It was already dark and they stumbled over the dead. They found the bodies of all victims and placed them on the floor of the house, including that of Clara Wilson at the other place. They found the little boy who had cried himself to sleep. He wailed, “Clara is sick. I am hungry.”

The two women told their story later at the hearing when about three hundred Indians were sentensed to death for the outrages committed. The two Indians who did not take part in the killing told the whole story and were among those who were pardoned by President Abraham Lincoln. The two who quarreled over the eggs and started the bloody carnival of death were included with the thirty-eight who were hanged at Mankato on the third day of Christmas, 1862. The little boy was adopted by a childless couple near Osseo, Wright County.

(Note from Carolyn Sowinski:)

Gunder's fence, which housed the nest of chicken eggs, was part of the story of the Acton killings. This fence was included in a drawing by a soldier in Company B of the 9th Minnesota Regiment. This soldier drew a map of the Battle of Acton (.jpg file) (pdf file) where 6 soldiers were killed and 15 wounded. The 9th Regiment later fought in the Civil War. Confederates captured Company B and many died at Andersonville Prison in Georgia.

In this drawing Gunder's fence is in the middle of the left side, it forms a square with soldiers camped within its perimeter. "Jones Place" is written just above the building.

Acton Township is located south of Grove City, Minnesota. The location of the Acton killings, which began the 1862 Dakota War, has a historical marker and is just west of State Highway 4. This is the location of "Jones Place" and Gunder's fence. The Battle of Acton, also depicted on the hand-drawn map, occurred about 2 miles east of this marker.

Thanks to Kurt Mankell for the map and the information about Company B of the 9th Minnesota Regiment.

Having now run two years ahead of my story, I will come back to the subject of this sketch.

In the fall of 1860, Sven Borgen and son Gunder one day hitched up the oxen and drove over to Robinson Jones’ place in Meeker County to get the fifteen bushels of wheat and bring them to the Kingston mill to be ground into flour. But this mill was so crowded with grists awaiting their turn that there was no prospect to get the wheat ground for a week. So our folks proceeded on to the Fairhaven mill. Here they had their grist ground during the night, but there was also a heavy snowfall. Nevertheless they started for home. There was much snow, the young oxen were tired, night was coming on, and the father said “it seems as if we will be left outside in the open and the dark night.” “No.” Gunder said. “I can see a settler’s house. We must aim for that place.” This they did and what a happy surprise! Here the father found a companion of his youth. Both were born at the same place, grew up together and were confirmed in the same class. They received a hearty welcome. Both knew that the other was in America, but not where he was located. And now chance had brought them together. Halvor Kjorn, for such was his name, said “unhitch your oxen for here is heart room, house room, stable room and hay.” It was like getting home. What a review the two men had of their experiences since last they met.

During the night there was another snow fall. They then decided to leave all of their load there except one sack of flour. But Halvor would not hear of their plans. He said, “Leave your oxen with me. I will take care of them. I will lend you two pair of skis to go home with, over a distance of about forty miles. Don’t torment your young oxen in all this snow.” They accepted the offer, and went home on skis.

Three weeks later Gunder Swenson started off on one pair of the skis and carried the other pair on his shoulder. The next morning he stared on the home trip with the oxen and the load of flour. The first night he stopped at Wheeler’s place at Diamond Lake. The next night found him across the lake at Joshua Gates place. Mr. Gates was the first superintendent of schools in the county. Much snow was encountered, it was tough going, and the boy was only in his 17th year.

The third day there was a thaw. The runners of the sled accumulated the snow so the whole thing was like a log. Gunder aimed for Burdick’s place, but his oxen became tired, darkness came on and it seemed that he would have to give up. But Burdick’s dog had heard him urging the oxen and made such noise that Burdick came out and found him and helped him to the place, but left the load on the prairie. In the morning the oxen could not start the sleigh. Burdick hitched up his larger oxen, but with the same result. They had to unload and cut out all that snow and ice to get the sleigh out. There he left the wagon box, making the load lighter for the oxen. He placed the grist on three rails.

By this time, the father, who had been worrying about his long absence, came sailing along on a pair of skis, and found him just south of Green Lake at Columbia (where Spicer now stands.) They proceeded and reached Nest Lake for the night, coming to the home of Samuel Stoner and Peter Thomson. “What kind of a load do you have?” was asked. Sven said, “Flour.” “Oh, God bless you. This is a godsend. We are out of flour. You must help us out with a sack. We have organized a gang of eight men with oxen teams with extra shovelers to open the road to Kingston mill, but the folks will suffer while we are doing it. We will get your wagon box at Burdick’s and bring that and the sack of flour when the roads are opened.” And Sam Stoner kept his word. In the morning they had a poor trail to Monongalia Beach to the place where Senator Lawson’s summer cottage is now. Then the road was across Lake Andrew, Middle Lake, Norway Lake to Thomas Osmundson’s place, the son-at-law and brother-at-law, who lived not far from where the Isle of Refuge is located. The oxen could not say how tired they were, but they showed it by laying down in the snow where they stood hitched to the sleigh. It was only two miles left, but they had to stop overnight. They got home the next morning after being a week on the trip to bring home the grist. That was stored away in the little log cabin, the result of the summer’s work of Gunder.

The sister, Ragnhild, married Chr. H. Engen. After all the tragedy of the Indian troubles were over, Gunder stuck to the pioneer place. He married Miss Gemine H. Negaard, 17, in 1871. They had thirteen children – seven sons and six daughters – Minnie (Mrs. O.A. Mankell of Willmar; Clara (Mrs. O. Berg) Sacramento, CA; Anne (Mrs. A.W. Quale) on the home farm; Lydia (Mrs. C.H. Grace) of Minneapolis; Helen (Mrs. F.A. Lamphere) Buffalo, SD: Mabel, deceased. The sons are Sven Henry, deceased; Sven G., Henry, and George of Norway Lake; Otto of Minneapolis; Gerhard of Spicer; William of Buffalo, SD.

Gunder Swenson has been blind eight years – the first two years he was cared for by his faithful wife. But he lost her by death, Sept. 6, 1927. Since then his daughter Anna has taken care of him, for which she deserves much credit. I called upon him often. The last time, on Sept 8, last. He asked me then “What time is it? It is night all the time to me.” I answered, “Ten o’clock am.” He said, “I am on the last lap of my journey now. I shall soon be across where I shall get my eyesight. I shall not live until tomorrow night.” And he was right. The next day, Sunday, Sept. 9, at 4:30 pm he was no more with the living.

Rev. Baalson sounded the right keynote when he said “He has been a good neighbor.” I can attest and okay that statement, for I have been close neighbors with him for sixty-eight years, without a single misunderstanding. He was neighborly and more. He was honest, upright and straight in all his dealings; always accommodating and more; strictly temperate, an earnest advocate and promoter of prohibition. No booze, no snuff-eating, no cigarette smoking or tobacco in any form. In that he was a worthy example to the young men of today.

The funeral was held the afternoon of Sept. 14. Services were first held at the home and then at the East Norway Lake Church. The pastor, Rev. Herman E. Baalson, officiated and conducted the last sad rites. The six sons acted as pallbearers. The honorary pallbearers were S.A. Syverson, C.A. Syverson, Halvor Thorson, S. Reigstad, Ole Stene and Gabriel Stene. There was a profusion of flowers and flower girls carried them in the procession.

Those attending the obsequies from a distance included the following: Mr. and Mrs. Ole H. Negaard, Mr. and Mrs. CM Negaard and Miss Ottina Negaard, all of St. Paul; Mrs. Lina Palmer, Mrs. Miller, Mr. Hendrick Johnson, all of Minneapolis; Mrs. Nellie Norin, Miss Lillie Noren, Mr. Gunder Osmundson, Judge G.E. Qvale, E.T. Qvale, Mrs. Delia Qvale, and Mr. W. Bourgette, all of Willmar; Mrs. H. Elkjer, of Bertha; Mrs. George Alvig of Montevideo; Mr. and Mrs. Sivert Osmundson, Mr. and Mrs. Harry Martin, Mrs. Frank Lundgren, and Miss Anna Stene, all of Spicer; Mr. and Mrs. Martin Negaard, Dr. and Mrs. Larben, Dr. and Mrs. Hans Johnson, all of Kerkhoven; Mrs. Minnie Hagen and son Wallace, of Murdock.

And now he sleeps alongside of his Gemine, his daughter Mabel, Baby Henry and his parents in God’s acre at the East Norway Lake Cemetery – the pioneer patriarch, Sven Gunderson Borgen.

These are a part of the life runes of Gunder Swenson. He was active in the gathering of refugees and getting ready for the exodus after the Indian massacre. On his horse with a gun he was a scout to watch for hostile Indians while the survivors were digging the large grave for the thirteen victims at Monson Lake. The workers had their guns ready for defense if the signal should have been given. But they were not molested at that time.

He was one of those who slept upon the bare ground in the open on the Isle of Refuge three nights. He helped to gather and load up all movables and round up all remaining cattle, for the flight eastward to St. Cloud and other places. He was among the first to return.

He was the last one who took part in those stirring times of trouble to go to his silent narrow chamber. There are two more living of those who were on the Island, but they were tiny babies at the time – Mrs. John Skare and Gunder Osmundson.

I have taken pains to write this sketch, and request its publication as written, for in my opinion not many deserve recognition as much as my good old neighbor, Gunder Swenson, a few of whose experiences I have set forth herein.

(G. Stene)

Gemine and Gunder Swenson (c1920) in front of their home on the south side of Lake Mary.

Gemine Negaard Swenson:

PIONEER WOMAN HAS PASSED ON: Norway Lake--It is our sad duty this time to chronicle the death of a highly esteemed pioneer lady, Mars. Gunder Swenson. Gunder Swenson and family, including the old pioneer parents, Mr and Mrs. Sven Borgen, were exceptionally fine neighbors. Over the period of sixty years of neighborly friendship, not a link of the chain was broken nor an unfriendly act known. The departure touches the very tender chord of sympathy for and with the bereaved ones. There was a time when there was a large bunch of happy youths around the hearthstone, but now they have spread and their homes are far apart. Everything changes in time as the years roll by. Mr. Swenson has now been blind for two years and cannot see the difference between night and day. Consequently his faithful wife and true companion has been his mainstay to attend to his needs and see that he was properly cared for.

Mrs. Gunder Swenson of Arctander has Answered the Roll Call from Over Yonder

Willmar Tribune

Written September 10, 1927

As a young man of seventeen, Mr. Swenson was one of the burial party which interred the remains of the thirteen unfortunate victims who were killed by the Indians at West Lake on August 20, 1862. For that reason I urged him to go along to take in the big doings at Monson Lake at the dedication of the park a few Sundays ago. The folks hesitated to permit it under the circumstances. I promised to relieve Mrs. Swenson of one day's care and undertook myself to see him through and see him back home safely. They both consented, and with his good wife greatly enjoyed the day. This was on August 21. On August 24, Mrs Swenson was taken sick. Everything possible was done for her but she grew weaker and weaker, and on Sept. 6 she passed over the dark waters of the Valley of the Shadow of Death, from whence none returneth. It was a sad blow to children, grandchildren, relatives and neighbors, but most severe of all was the blow to the blind husband. He said, "Now I will have no one in this world to care for me!" I said to him, "Take a look on the bright side, and cease to worry. Your children and grandchildren are an ample guarantee that you will not be lacking of the care you need. You will find that they will be proud of their blind father and grandfather."

The funeral took place on Sept. 10 at one o'clock from the home and at two at the church. The floral tributes were simply the best that could be obtained both in quantity and quality, and were well taken care of by Julius Jacobson, the undertaker. Rev. H.E. Baalson conducted the services and preached on of his usual good sermons for the occasion. A duet was sung by Rev. and Mrs. Baalson, and solos were sung by Miss Lillie Noren, both at the home and at the church. Organist Henry Severeide presided at the organ and accompanied the singers. Six sons were the active pall bearers. The honorary pall bearers were Messrs. Halvor Thorson, Engvald Hanson, Reier Stai, A. H. Gordhamer, Edward Hauge, and G. Stene. The flower carriers were the Misses Edna and Alice Mankell, Florence, Ruby, Helga and Eleanor Swenson.

Biographical

Gemine Negaard Swenson was born at Storelvdalen, Osterdalen, Norway, April 9, 1854. There she grew up to womanhood. With parents and other members of the family she emigrated to America in 1870, arriving in Willmar on July 4th. The family located in Arctander township, where she continued to live till her death. She was married to Gunder Swenson on December 30, 1871. This marriage was blessed with fourteen children, as follows: Sven who lives at Norway Lake; Henry, died in infancy; Minnie, Mrs. Oscar Mankell of Norway Lake; Henry of Nest Lake; George of Norway Lake; Clara, Mrs. O. M. Bergh of California; Anna, Mrs Axel Quale, on the home place; Mabel, deceased; Lydia, Mrs. C. H. Bruce, Minneapolis; Helen, Mrs Lamphere, Buffalo S. Dak.; Otto, Minneapolis; William, on the home farm; Melvin and Gerhard of Norway Lake.She is survived by the following sisters and brothers: Tomine, Mrs E. P. Truedson, Puyallup, Wash.; O. H. Negaard, assistant postmaster at St. Paul; Martin Negaard, hotel man at Kerkhoven; Halvor Negaard of St. Paul. Three sisters have passed on before: Gjorand in Norway; Martha, soon after arrival in this county; and Hannah died in Chicago eleven years ago. There is a large number of other relatives and friends to mourn her death. Thirty-two grandchildren have lost their good grandmother. She was at peace with everybody and was content to submit to the will of God. All the children except Otto and Helen were present at the funeral of their mother; also the three brothers, Clarence Negaard, a nephew and wife of St. Paul, and C. H. Bruce of Minneapolis, a son-at-law.

An unusually large assemblage had met to pay homage and their last token of respect to one of the most highly esteemed women of Arctander, where she had lived fifty-six years and where he dust now sleeps.

Mrs. Swenson! Oh how lonesome

When we spy your vacant chair!

No more cheer within your bosom,

Hidden is your silvery hair;

Heart is stilled, your eyes are dim,

Cold your hand and chilly limb;

But you said, "Meet Me up Yonder."

"Children mine, be good to father;

He is helpless, deaf and blind;

Oh, grandchildren, help each other

To console his troubled mind.

Take him by his hand and arm;

Show him that your heart is warm;

Cheer him sister, cheer him brother,

Show him that you love Grandfather."

--Gabriel Stene, September 10, 1927